Anthropogenic climate change is now influencing the population dynamics of many species. Its impact is often mediated by effects on the local environmental conditions that determine key biological processes such as fecundity and mortality. For animals living in seasonal environments in temperate regions, individuals usually suffer most mortality over winter, and winter mortality may therefore contribute considerably to the dynamics of wild animal populations. An understanding of how climate change affects winter mortality is therefore critical for providing insights into how natural populations are being affected by current climate change, and hence for informing appropriate management and conservation strategies.

The effects of climate and climate change on winter mortality in wild animals may be complex. First, minimum and maximum temperatures may affect individual mortality in different ways, each of which depend on species-specific thresholds. Secondly, winter mortality may also depend on levels of precipitation, and its interaction with temperature. Lastly, winter mortality may also be affected by climate at other times of year, via longer-term ‘carry-over’ effects. For example, the increasing frequency of extreme high-temperature events (i.e., heatwaves) and droughts during the breeding season of previous summer may have long-term implications for survival through the winter.

Long-term studies provide a valuable means with which to disentangle the complex impact of climate on winter mortality in wild animal populations. However, to date, relevant studies have frequently been carried out on annual time scales, considering population-level annual average rates of mortality, and often based only on monitoring conducted during the breeding season.

Superb fairy-wrens (Malurus cyaneus), photo by Geoffrey Dabb.

In this study, we used 27 years of individual-based weekly census data to investigate the effects of climate on mortality of superb fairy-wrens (Malurus cyaneus) in south-eastern Australia. The combination of year-round censussing and a near-perfect detection rate in our long-term study allows us to pinpoint the time of death of all individuals to a given week, and then to relate it to recent weather patterns within and across years.

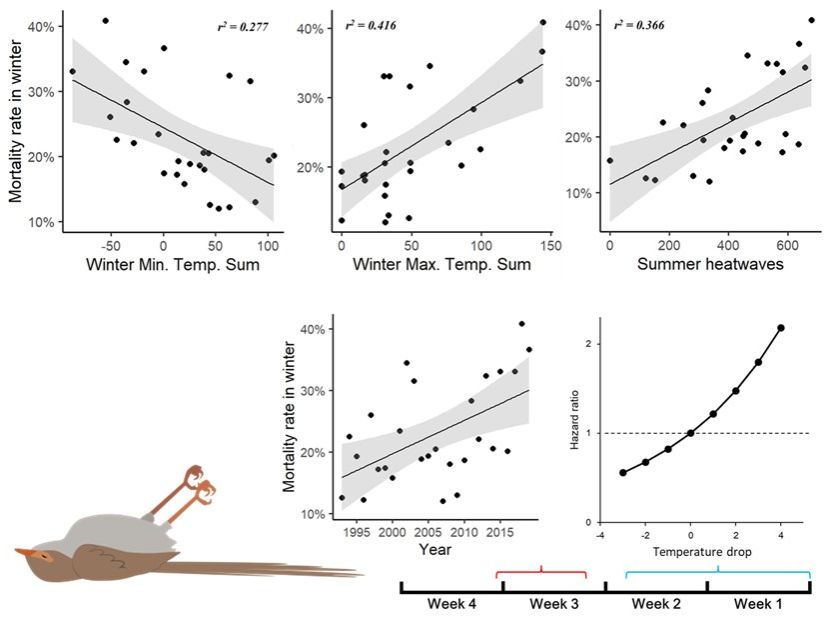

We found that mortality outside the breeding season nearly doubled over a 27-year period. This non-breeding season mortality increased with lower minimum (night-time) and higher maximum (day-time) winter temperatures, and with higher summer heatwave intensity. Fine-scale analysis showed that higher mortality in a given week was associated with higher maxima two weeks prior and lower minima in the current fortnight, indicating costs of temperature drops. Increases in summer heatwaves and in winter maximum temperatures collectively explained 62.6% of the increase in mortality over the study period. Our results suggest that warming climate in both summer and winter can adversely affect survival, with potentially substantial population consequences.

Our study showed the effect of winter temperature and heatwaves in the previous summer on the increase of adult mortality rate in the non-breeding season. Individuals show higher mortality after experiencing one warm week following two cold weeks (i.e., large tempearure drops).

This work is published in Science Advances entitled “Winter mortality of a passerine bird increases following hotter summers and during winters with higher maximum temperatures”. Dr. Lei Lv (currently Senior Research Scholar in Southern University of Science and Technology) from Prof. Yang Liu's group in School of Ecology, Sun Yat-sen University, is the first author. Dr. Lei Lv and Prof. Yang Liu are corresponding authors. Prof. Loeske E. B. Kruuk (from University of Edinburgh), Prof. Andrew Cockburn and Helen L. Osmond (from The Australian National University), and Dr. Martijn van de Pol (from James Cook University) joined this research. This study was supported by the Australian Research Council.

Link to the article: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.abm0197